It was Sunday. The day for rest, and Sila, having attended mass at St. Augustine Church as she always did, now had the afternoon free. For Sila, Sunday in New Orleans was devoted to two things: the Holy Father in the morning and the few hours freedom she enjoyed before the cannon fired on Sunday night.

She heard the drums as soon as she reached Rue de Rampart. Rather she felt them, cinquillo rhythms and djembe beats that captured her breath, throbbing deep in her chest. This rumbling would guide her footsteps for a few paces and then alternating, the smaller tam tams would respond, their complex tresillo and clave patterns hovering higher in the air, ricocheting in her ears and bouncing off walls. Why do these sounds call to her? Is she seeking community or do these pulses touch her on a more spiritual level? She did not know. She only knew that she came to the Square each Sunday to hear the drums. To inhabit their beat and surrender herself to a feeling that felt a lot like freedom.

The crowd grew thicker as she approached the Square and she turned up Rue de St. Peter’s toward the market area, seeking out her favorite vendor, an old Chitimacha woman who customarily took her place under the limb of an oak tree that corkscrewed out from its trunk until the tips of its branches touched blue sky. Sila had been buying herbs from this woman since she was a little girl, ever since her mother had first met her on their first trip to the Square. The old woman was known for her variety of herbs and the quality of her ginger root. She only visited the Square once a month, by way of the Mississippi River, and regularly sold out of her goods quite early in the day. Sila knew this so made an extra effort to arrive early.

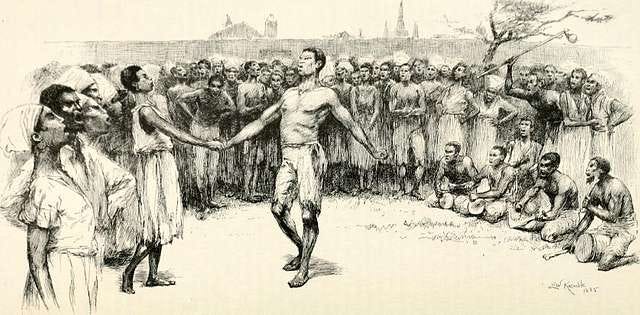

Sila reached up and tightened her tignon, looking out over the crowd. Rings of dance circles surrounded her, each layered with dancers, singers, and spectators, waiting for their turn in the round. Over the pulsating rhythm of the drums she could hear a few fiddles in the distance, as well as the light piping of some reed quills. The Square was especially full today, a sight that pleased her. She took a step back to allow for a rickety old wagon to pass in front of her and then pressed on. It was then, over the din, that she heard someone call her name.

“Sila!” the voice called again, this time nearer, and through the crowd she saw Victor, carrying a trombone under one arm as he waived to her with his free hand. He was formally dressed in a white shirt and black coat, but his tie hung loose, indicating an earlier battle with the heat that apparently, he had lost.

“Victor,” Sila said. “How are you?”

“Fine...fine...I’m on my way to the Orleans Ballroom. François asked me to sit in on one of his sets. His way of introducing me around town before Carnival when the steady work begins.” He suddenly paused and dropped his gaze nervously towards his feet. “I saw you earlier at church but didn’t have a chance to speak with you before you hustled out of there. Was hoping I’d run into you again...”

Sila stood fidgeting and tried to force a smile. “Yes, well...”

“Where are you going?”

“Oh, the market...I come most Sundays if the Monsieur is out of town. I like to gather herbs to dry so I can make ointments or teas. It was something my mother taught me to do...” Sila knew she was prattling on but had no means to settle her nerves. She reached down and grabbed a tie that had fallen loose from her skirt and began to wring the ribbon through her fingertips.

Victor smiled sympathetically, his bright calming eyes locking her gaze. He shifted his weight and moved his trombone to his other arm. “Then may I escort you?”

“Oh no...” protested Sila. “You have to get to the ballroom and really, this can’t be interesting to you.”

“The show is actually tonight,” countered Victor. “I was only getting there early...well, because as a new arrival to this city, I frankly have nothing else to do. But as fate would have it, I lucked out and now I do...to serve as your escort. You wouldn’t dare deprive me of this display of chivalry, would you?” he said with a wink.

Sila smiled and shook her head. “Really, I’m looking for herbs. There must be a thousand things you would rather do today…”

“Actually, you’d be doing me a favor. My grandmother loves dried lavender. I planned to see her later this week and this would provide me the chance to bring her some.”

It was clear to Sila that her protests would continue to fall on deaf ears so with a nod to Victor she said, “Alright then,” and began to walk on.

For several moments they walked in silence, taking in the sights and the music of the Square, until Victor suddenly forced an awkward interruption. “It’s so great to be back in town. It’s been years since I’ve been down here. I was worried that they had shut it down again.”

“They try to…but we always get the best of them.”

Victor nodded. “I hear these days they require passes.”

Sila nodded and slipped hers out from her skirt pocket. “You do…,” she said showing it to Victor. “...but they are pretty easy to get. In fact, your uncle gives me mine, every month. He signs on behalf of the Monsieur,” she said with a slight smile. “Of course, please don’t let anyone know about this.”

“Good for him,” said Victor. “And of course, your secret is safe with me. I’m not surprised. The last thing François would ever do is to allow someone to tell him when and where he could blow his horn. In his mind he earned the right to do whatever he damned well wanted to do after fighting off the British with General Jackson ...” With that Victor quietly added, “Pardon the language, madam.”

Sila nodded and smiled.

Victor abruptly stopped and turned to face her. “Actually, can I see that thing?” he asked.

She again pulled out her pass and handed it to Victor. “You know just yesterday my mother told me to start carrying papers myself. Said I’d need to be able to prove I was a free man...you know, just in case I get stopped by the police or something. Me...Victor Dupre, born to a free mother and free father. The grandson of a manumitted slave. This town has changed...or maybe it hasn’t. Maybe I was so young back then I didn’t know any better.” He looked down at the pass and pointed at the name. “Your name is Sila…why does it say Maggie?”

Sila rolled her eyes. “That’s the name the Monsieur gave me. Maggie was the name of his favorite hunting dog...she died right before he bought me. How, I’ll never know, but he said in some way I reminded him of her. He has a painted portrait of that dog in his office. A smelly hound dog.” Sila paused and looked away. “Sila is the name my mother gave me,” she said finally.

Victor shook his head, kicked a large tree root, and handed the pass back to Sila. “What I want to say right now I just can’t…not in the presence of a lady,” he said, quietly trying to quell his anger. “But Sila, that is wrong. In so many ways.”

For a few moments they walked in silence as Victor tried to compose himself. While Victor’s genuine outrage at the Monsieur’s treatment of her strengthened her, Sila was also shocked by his quick temper. Besides François, no one had ever spoken so intimately with her and it frightened Sila. This was not something she wanted to allow in. To drop her guard and feel his softness while the rest of her life was so cruel? No, she could not recover from that so best not to let him in in the first place.

“No matter, I think I’ve gotten used to the name anyway,” she lied. “And how long were you in Paris?” she asked, changing the subject.

“Twelve years,” he said while studying the fingering of a nearby clarinetist. “I left New Orleans when I was fifteen. A lifetime ago.”

“And you have been away the whole time?”

“Mostly…two years ago I came home for Christmas. But mostly I stayed in Paris. I live with a family there. Actually, they are my tutor’s family. They are wonderful people with a son my age, so I wasn’t lonely.”

“I can’t imagine,” Sila said. “Paris seems so far away.”

“Oh, it is…but what a city! Sila, you’d love it. The music, the opera! It’s why I left New Orleans. The music in this town, its exceptional, but my parents wanted me to learn from the best.”

“But to Paris…I mean, like you say, we have such talented musicians here. Why Paris? How does that even happen?”

Victor smiled. “Felippe Cioffi…”

“And who’s that?”

Sila’s interest pleased Victor, who at long last had decided he was finally getting somewhere in his pursuit. “He plays the trombone. Spent a good bit of time in New York. Then moved down here. He’s brilliant. One night my parents saw him at the St. Charles and fell in love with his sound. Up until that point I had just played the violin. And I was gifted, as they loved to say. I’d studied under many excellent private tutors, but after Mr. Cioffi told my parents about the Conservatoire de Paris and the teachers there, my die was cast. At fifteen they felt I was finally old enough and sent me off to Paris, completely alone.”

“Do you still play the violin?”

“On occasion, when asked,” he paused and then quickly added, “I’d play it for you.”

Sila blushed and demurred, “But don’t you enjoy playing the violin?”

“I do,” Victor added, undaunted. “But I have too much of my uncle in me. I like to blow a horn.”

Sila mused. “My father played the violin,” she said quietly. “Quite well, actually.”

“He did?”

She nodded.

“What was he like?”

She paused. “My father? Oh, he was a wonderful man. Very kind. A very loving father. It was he who taught me to read…he was adamant that I know the masters. And poetry—to this day, I can recite most of Shakespeare’s sonnets by memory.” Sila paused and then quickly whispered, “Please don’t tell anyone though.”

“Of course not,” Victor said, “And who taught him to read?”

“Oh, I don’t know. Tutors, I guess. You see, my father owned the plantation we lived on. But he was an honorable man…,” she added quickly, “and I’m certain he loved my mother. He was nothing like the Monsieur…” She paused, hating the bitter taste of that man’s name in her mouth. “My father’s first wife became ill, and he bought my mother from his neighbor to nurse her back to health. She was known around Jefferson Parish for her herbal treatments. The mistress, though, she died quickly. It was like her illness just swallowed her up…swallowed her up whole. My mother, the doctor, no one could help her. After she passed, my mother stayed on to care for my father. His son…he had a family and lived on another plantation up the river. He scarcely visited though, which left my father alone in the big house. I’m not sure exactly when my mother had me, but after she did, most of the time it was just the three of us. My childhood…it was happy. No one told me I was a slave until the day he died.”

Victor eyed Sila with skepticism. “I’m surprised,” he said. “You talk as if you actually miss it.”

“I guess I do,” Sila said. “I mean I was a little girl. I didn’t know anything about the world. I didn’t much like it when his son dropped by. They quarreled about us a lot. But eventually it just got to the point that if I saw that man riding up, I’d just run out to the barn and hide.”

Victor nodded, “So, what happened after your father died?”

In the distance was the grove of trees with the corkscrew limb and Sila knew they were getting close. “Well, in his will my father ordered that my mother and I be granted our freedom. We were to be given some money to live on and our manumission papers. His son…”

“…your brother,” Victor added.

“Yes, my brother. Anyway, he contested my father’s will. Said my father wasn’t in his right mind when he wrote those directions. Mind you, everything else in that will was just fine and the judge was happy to honor those gifts, all of which, of course, went to my brother. It was just my father’s desire to free my mother and I that my brother took issue with. The judge agreed and about a week later we were auctioned off at the Exchange. I was told later that my brother used the money he got from the sale to buy a horse he’d been eyeing.”

Again, Victor began to quietly fume while considering what, if anything, he should say. He stood for a few seconds in a state of ambivalence and then just couldn’t stop himself. “Sila…I know I don’t know you well enough to say this. And I certainly don’t want to disrespect you and what is clearly a genuine love for your father…”

“Yes, I did love my father. And he loved me.”

“Yes… but Sila… I mean, how can you carry on like that?”

“Like what?”

“Like the man did nothing wrong?”

“Well, he was my father and he treated me well. To me, he was a good man…”

“But Sila, that’s just it…he wasn’t. He wasn’t a good man. Yes, he might have been kind to you and treated you like a daughter. But at the end of the day, he could have freed you guys while he was alive and he didn’t. Something always stopped him. Think about that.”

“Victor don’t.”

“But Sila, why? What stopped him? Why did he need to own you? That choice…his inaction…especially with a son like that—I’m sorry, but that is not the mark of a good man. Knowing that when he dies, you’d be vulnerable to the whims of that son and the flimsy pages of a will he hopes will be honored by the Louisiana courts? Jesus, Sila, how can you not just be furious with him.”

Sila dropped her eyes. “I don’t know Victor,” she said, trying to lower her voice so as not to cause a scene. “He was my father. I don’t know why he did what he did, and yes, I’ve been angry at times. But some of my fondest memories were with him. That period in my life…it’s the only time I’ve ever been happy. During those days, I felt like a whole person.” Despite her protestations, however, Sila knew there was no way to defend her father. Victor had sized up the situation quite adeptly. And she was pained by her father’s betrayal. “I do understand your anger, but I’m…” she paused and took in a long breath. “It’s just that I’m afraid that if I actually got angry with him…angry like you are now…that I’d destroy those memories. And I’m afraid what that would do to me. At this point, Victor, they’re all I have.”

The shame she held in these words made her weak. She turned back down the path towards the corkscrewed tree branch and saw the old Chitimacha woman seated on her blanket just ahead. Surrounding her were dozens of intricate baskets full of different roots and rattlesnake rattles, and leafy plants of every size and description.

“Here we are,” Sila said in relief.

The old woman nodded at Sila and Victor as they approached, reached down into her leather satchel, and brought out a batch of dried cattails. Some of the large brown flowers had crumpled over the long journey and the old woman tried to straighten them, seemingly embarrassed. After removing some of the more damaged stalks, she handed the plants to Sila, pointing towards her belly.

“Thank you,” Sila said to the old woman, who smiled in response. This was how they always communicated, with hand signals and small gestures. Despite these impediments, though, they had developed and maintained a mutual admiration of each other over the years and this admiration in some ways had developed into what could only be called a friendship.

As Sila looked over the plants lying on the blanket, the old woman frowned and gestured at the hand-shaped bruise along the inside of Sila’s wrist.

“Oh, it’s nothing,” Sila said with a half-smile, while pivoting her blackened bruise away from Victor’s sight. She reached to pull her sleeve down further, but with the bruise being so large, some of it remained exposed.

The old woman lifted some plantain leaves from a batch on her blanket and using river rocks and honey, pounded the leaves into thick poultice. With a nearby stick she scooped up the mixture and gestured to Sila to apply it to her bruise.

Sila shook her head and waived the stick away. “No please,” she said quietly.

But as Victor returned with some lavender, the woman gestured again.

“What’s going on?” he said, and then noticing the bruise, he looked at Sila. “What’s that?”

“Nothing,” Sila said, yanking back her arm.

“Sila,” Victor said, pointing at the bruise. “That’s not nothing. Who did that to you?”

The old woman stared at Victor and seemingly pleased with his acute concern, nodded in agreement.

“No one,” Sila said, trying to muster a laugh. She grabbed her cattails and some gingerroot and placed them in her small bag. “Actually, I did it to myself. Last week when I was at the market, I wasn’t watching where I was going and tripped over a vegetable crate.”

Victor persisted. “It was Monsieur Dubois, wasn’t it? He did that to you. That bastard…”

“Shhhh,” Sila whispered, darting her eyes across the crowd. Although she’d never seen the Monsieur or any of his friends at the Square—and especially on a Sunday—she knew she couldn’t be too careful. At any time, a sighting of her could be reported back, and the Monsieur was especially cruel when punishing perceived acts of independence. Victor’s mention of his name and moreover, out in public, terrified her. “Of course not, Victor. Like I said, I tripped over a crate…that’s all.” She quickly began to walk away, furious with herself. Normally her trips to the Square were so silent…she could sneak in and out and no one would pay her any attention. But on this trip Victor had so carelessly drawn attention to themselves. The acts of the unthreatened, she thought, shaking her head. Didn’t he understand the danger he was putting her in? If the Monsieur found out she was there and—god forbid—with a young man. Sila shuttered at the thought of what the Monsieur would do to them.

“I have to go,” she said suddenly, and not waiting for his response, ducked behind a huge crowd of revelers, and soon, out of sight.